|

Biographical Note |

| The Edward Carpenter Archive by Simon Dawson |

|

Biographical Note |

| The Edward Carpenter Archive by Simon Dawson |

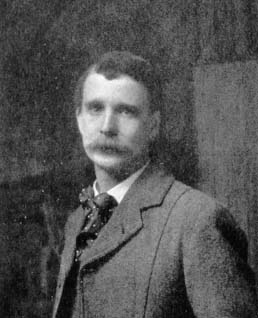

Edward Carpenter was a pioneering socialist and radical prophet of a new age of fellowship in which social relations would be transformed by a new spiritual consciousness. The way he lived his life, perhaps even more than his extensive writings, was the essence of his message. It is perhaps not surprising that his reputation faded quickly after his death, as he lived much of his life modestly spreading his message by personal contact and example rather than by major literary works or through a national political career. He has been described as having that unusual combination of qualities: charisma with modesty. His ideas became immensely influential during the early years of the Socialist movement in Britain: perhaps Carpenter's most widely remembered legacy to the Socialist and Co-operative movements was his anthem England Arise! but it is his writings on the subject of homosexuality and his open espousal of this identity that makes him unique.

Edward Carpenter was born in Brighton on 29 August 1844 (at 45 Brunswick Square) into a comfortable, middle-class family. There were 10 children in total: six girls and four boys; by the time Edward was in his teenage years he was the only boy along with his six sisters in the house. The family took a year abroad in Versailles in 1857 and the other boys took up careers in the armed services.

Edward's path was more academic and he took the orthodox path to University, entering Cambridge as an undergraduate in 1864. Academically successful, Carpenter had the opportunity in 1867 to become a fellow of Trinity Hall, Cambridge, following the resignation of Leslie Stephen, Virginia Woolf's father. As was required then, he was ordained into holy orders of the Anglican Church. He adopted the clerical life as a convention rather than out of deep conviction, but conscientiously carried out his duties as curate at St. Edward's Church, Cambridge.

In 1868, he received a copy of Walt Whitman's poems Leaves of Grass. Whitman's democratic poetry provided the spark that set Carpenter on the path of socialism and which led to the extraordinary changes in his life. In 1873, while returning from Cannes, a vision of a different life flashed before him:

"I would and must somehow go and make my life with the mass of the people and the manual workers".

He resigned from his clerical fellowship at Cambridge, rejecting the comfortable way of life that it provided, and set off to work for the University Extension movement in the North of England. There followed several years of travelling, lecturing on scientific subjects, but the work he did for that idealistic movement still did not satisfy Carpenter's desire for an immersion in the life of working people and striving for the transformation of their lives

His lifelong connection with Sheffield had begun during his lecturing days, and strengthened when he met Albert Fearnehough, a working class man in whose house Carpenter lodged (as well as Fearnehough's wife and family). The death of his parents in 1881/82 left Carpenter with a considerable inheritance with which he bought a 7 acre smallholding at Millthorpe, in the countryside near Sheffield. Soon after, a house was built there and in 1883 Carpenter moved in with Fearnehough and his family.

The country retreat at Millthorpe became home for Carpenter, his friends and lovers, and eventually became a place of pilgrimage for large numbers of admirers during the following 40 years. Millthorpe and its inhabitants became a symbol for the new way of life that Carpenter developed there: a 'simplification of life', manual work on the land, sandal-making, vegetarianism and the breaking down of class distinctions.

That same year (1883) also saw other significant events in Carpenter's life: the publication of the epic poem cycle called Towards Democracy, which became his most well known work, and his first contact with the nascent Socialist movement. Throughout the rest of his life, Carpenter supported a broad Socialist movement without ever being committed to a parliamentary political party or any narrow doctrine. His aspirations were always more inclined to Anarchism than to the Labour Party. In the early days of British Socialism, he took the side of William Morris when he left the Social Democratic Federation in 1884 to form the Socialist League. The League saw the task of socialism in terms of creating a new inner consciousness for all people rather than the more strictly economic doctrines and struggles which the SDF began to focus on.

Another important strand of Carpenter's thought also had its roots in these years: his study of eastern religions, particularly the Bhagavad-Gita. During the 1880's there was much discussion of Eastern mysticism, particularly with the rise of the Theosophical movement. Carpenter became determined to discover more about Hindu thought, direct from its source, and in 1890 he fulfilled a long-held ambition and travelled to Ceylon and India to spend time with the Hindu teacher called Gnani, who he describes, along with his Indian travels, in the book Adam's Peak to Elephanta.

Carpenter's synthesis of Eastern religion and Socialism, produced a special brand of 'mystic socialism' which became the vehicle for a whole series of idealistic campaigns, some of which seem absolutely up-to-date in their concerns (for example campaigns against air pollution, promoting vegetarianism and opposing vivisection ), whereas other concerns have become so much a part of everyday life now that the campaign for them is a quaint reminder of long-gone, Victorian days (the adoption of 'rational dress' including the making and wearing of sandals). Vegetarianism, air pollution, 'rational dress', the 'simplification of life', sandal-making and wearing and nudism were eventually to be rejected by many in the Labour Party as cranky beliefs.

Above all, the aspect of his life and writings for which Edward Carpenter has achieved lasting fame, and which caused him the most problems with the more conventional section of the Labour movement, was that of sexuality, in particular his own homosexuality. Carpenter had been aware of his own 'affectional nature' almost all his life, but the strong forces of conventional morality prevented their expression until comparatively late in his life. At University, he had a close friendship with Andrew Beck (later Master of Trinity Hall) which had 'a touch of romance'. Beck eventually ended the friendship and denied the attachment, causing Carpenter great emotional anguish. Later years saw a series of close friendships with men, usually with an unexpressed undercurrent of sexual longing. On occasions Carpenter would resort to visiting male prostitutes in Paris.

It was only after settling at Millthorpe that Carpenter really felt able to express his emotional attachments to men. He had a relationship with George Adams, who lived with his wife Lucy at Millthorpe, but this came to an end when George Merrill finally came there to live permanently in 1898.

Carpenter had met Merrill on a train journey in 1891, shortly after his return from India. Merrill came from a poor working-class family in Sheffield and the two rapidly developed a romance that was to last for nearly 40 years. Two men, of different classes, living together openly as a couple, was almost unheard of in the 1890's and it was often assumed that George was 'just' the servant: indeed, he was legally registered as exactly that.

It is clear that Merrill was a very different character to Carpenter: plain speaking, flirtatious and fond of a drink, their association caused much comment in the early days. But despite the atmosphere of legal persecution following the Wilde trials of 1895, they lived a life together in their rural retreat largely undisturbed. As the years went by they became inseparable and together established Millthorpe's reputation as a retreat and place of pilgrimage for a procession of visitors, including admirers, devotees and cranks.

John Addington Symonds had already privately published his pioneering books on homosexuality in the 1880's which were distributed among a small, selected group of people, including Carpenter. On Symonds' death in 1893, Carpenter perhaps saw the mantle passing to him and within a couple of years made his first attempt to publish on the subject with the pamphlet entitled Homogenic Love, also privately published. But the timing was unfortunate: it co-incided with Oscar Wilde's imprisonment and resulted in the pamphlet's exclusion from his 1896 collected writings on sex and marriage called Love's Coming-of-Age. As Carpenter later wrote: 'the Wilde trial had done its work…'

By 1908 a new milestone was reached with Carpenter's publication of a collection of his essays entitled The Intermediate Sex which was the first generally available book in English that portrayed homosexuality in a positive light rather than as purely a medical or moral problem. It was regularly reprinted and remained for decades as the crucial text in English that gave information, hope and support for homosexuals. In the final essay in the book, entitled 'The Place of the Uranian in Society', Carpenter makes this remarkable statement, almost dislocated out of its time, a full 60 years before the modern gay liberation movement came into existence:

"The Uranian people may be destined to form the advance guard of that great movement which will one day transform the common life by substituting the bond of personal affection and compassion for the monetary, legal and other external ties which now control and confine society".

A prophet, indeed, of a gay identity which then had hardly even begun to form.

Intermediate Types among Primitive Folk, published in 1911, was another important book on homosexuality which took a cross-cultural approach to the subject and remains a pioneering book on the role of the 'intermediate sex' in non-European cultures. Influenced by his study of Eastern philosophy, Carpenter emphasises the special spiritual role that many cultures reserve for homosexual or transgendered people, such as:

'the priest, medicine-man or shaman, the prophet and the diviner, the artist and craftsperson and the true scientist, successor to the tribal observer of the stars and seasons, medicine and the herbs'.

It is remarkable that Carpenter always avoided any public scandal or disgrace of the sort that overtook Oscar Wilde at that time. Although Carpenter made no secret of his relationship with George Merrill, he remained circumspect in his writings and lived in the relative isolation of the Derbyshire countryside. His books avoided prosecution despite having been investigated by the police on more than one occasion.

Carpenter's later years were characterised by his continued writings on pacifism, socialism, and trade unionism and he became a hero to the first generation of Labour politicians. During the short-lived Labour government in 1924, Carpenter's 80th birthday was marked by a commemorative greeting signed by every member of the Cabinet. For reasons which have never been clear, Carpenter left his beloved Millthorpe in 1922 (where he had expressed a wish to be buried) and moved with George to Guildford in Surrey. George Merrill died in 1928 and Carpenter himself a year later. They are buried together in a grave in the Mount Cemetery, Guildford.

Carpenter's literary and political influence was wide and deep, and is only just beginning to be explored. E.M. Forster was a close friend of Carpenters and famously names George Merrill as the inspiration for his novel Maurice. He had visited Carpenter and Merrill at Millthorpe on several occasions: once, in 1913, Merrill:

"touched my backside - gently and just above the buttocks. I believe he touched most people's. The sensation was unusual and I still remember it, as I remember the position of a long vanished tooth. He made a profound impression on me and touched a creative spring".

Despite never meeting in person, Carpenter's influence on D.H. Lawrence's writings was profound. Lawrence read the manuscript of Maurice (which remained unpublished for more than 50 years) and Lady Chatterley's Lover can be seen as a heterosexualized Maurice.

Carpenter was involved in the early days of the first 'progressive' school in England at Abbotsholme in Derbyshire with Dr. Cecil Reddie, which in turn inspired the foundation of schools such as Bedales and Gordonstoun. Another strand of influence is on 20th century town planning: Raymond Unwin, the architect remembered as father of garden cities, who was an associate of Carpenter's in the early days of the Sheffield socialists

During the depression of the 30's and the triumph of the Labour Party after the Second World War, Carpenter's brand of socialism became deeply unfashionable, and eventually embarrassing. It is quite clear who George Orwell was thinking of, when in The Road to Wigan Pier (1937) he condemns 'every fruit-juice drinker, nudist, sandal wearer and sex maniac' in the Labour Party. It was not until the emergence of the modern feminist and gay liberation movements of the 60s and 70s that Carpenter's ideas began to appear more relevant again. 'The personal is political' was one of the essential phrases of those movements and one that was also central to Carpenters' philosophies.

By the late 1970s, the rediscovery of Carpenter led to feminist Sheila Rowbotham publishing the book Socialism and the New Life and gay playwright Noel Grieg writing a Gay Sweatshop play on Carpenter entitled The Dear Love Of Comrades. Nevertheless, Carpenter's works remained largely out of print and knowledge of his influence confined to a relatively small circle. By the mid 1980s a group of radical gay men, inspired by ideas of community and personal growth, formed a national gay network, naming it the Edward Carpenter Community; this now has about 800 members.

Carpenter's influence on the early development of the gay liberation movement has been profound, if not always well recognised. Through the 'silence' that descended on the subject for more than 60 years after the Wilde trial, Carpenter's books remained a lifeline for many isolated gay people who found no other public representation or acknowledgement of themselves. The pioneer of gay liberation in the USA, Harry Hay, was deeply affected by his discovery of a copy of Carpenter's The Intermediate Sex in a library in 1923, when he was eleven. Hay describes reading the book as an 'earthshaking revelation', which had a profound effect on his life. In 1950 Hay founded the first modern gay political group, the Mattachine Society. In the 1920s, the black American poet Countee Cullen obtained a copy of Carpenter's poetical work Ioläus. He wrote:

'It opened up for me soul windows that had been closed; it threw a noble and evident light on what I had begun to believe, because of what the world believes, ignoble and unnatural. I loved myself in it'.

Throughout his life, Carpenter never ceased to express his esteem for, and indebtedness to, the American democratic poet Walt Whitman, who had provided him with his first great inspiration with Leaves of Grass. In 1888 Whitman wrote about Carpenter in a letter to Horace Traubel:

"Edward was beautiful then — is so now: one of the torch- bearers, as they say: an exemplar of a loftier England: he is not generally known, not wholly a welcome presence, in conventional England: the age is still, while ripe for some things, not ripe for him, for his sort, for us, for the human protest: not ripe though ripening. O Horace, there's a hell of a lot to be done yet: don't you see? A hell of a lot: you fellows coming along now will have your hands full: we're passing a big job on to you"

Chushichi Tsuzuki's invaluable and long out of print biography of Edward Carpenter is now available again. It is a highly readable and useful way of gaining deeper insight into Carpenter's life.

Follow this link.